As investors launch legal action against NAS 2016-1 Stalking Horse bidder, AWG issues Statement of Principles on Remedies in Structured Financing with Shared Security.

In March 2021, Airline Economics published an article based on the investor reaction to Stalking Horse bid launched by VMO Aircraft Leasing (VMO) – the new leasing company set up with the backing of Ares’ Private Equity Group in January 2021 – for the ten Boeing 737-800 secured under Norwegian Air Shuttle’s (NAS) Enhanced Pass Through Certificates (EETC), Series 2016-1. In that article, many industry sources warned that there would be an investor and industry reaction and now it has been confirmed that the investors concerned – Hudson and CarVal – have launched litigation against Ares Management, VMO Aircraft Leasing and Wilmington Trust in a New York court.

The complaint – Hudson et al v Ares et al – brings seven courses of actions against the defendants, primarily claiming they violated Section 9-610 of the New York Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), which requires all aspects of a foreclosure sale to be commercially reasonable, and claims breach of contract of the EETC indenture agreement and the intercreditor agreement, while Wilmington Trust is also accused of breaching its fiduciary duty in its role of trustee.

The complaint alleges that the foreclosure sale of a fleet of ten Boeing 737-800 aircraft was a “sham” that was designed to deprive the investors of any recovery and allow VMO Aircraft Leasing to obtain the aircraft at a discount of $50 million to its recently appraised market value. The complaint reveals that as part of its restructuring plan, NAS had offered to enter into new long-term leases for the entire fleet, with terms described as “valuable” by the investors, in January 2021 and in fact continued to fly the aircraft during, and throughout, the foreclosure sale process. The complaint also argues that the fleet was estimated to be worth nearly $300 million as of February 2021 and that the “conservative” average valuation of $270 million assumed there were no leases attached even though NAS had made the new offer for revised lease terms. Rather than re-leasing the fleet to NAS or orchestrating a “commercially reasonable sale”, the investors argue that Wilmington Trust followed the direction of ACOF and ASOF (which are private equity funds managed by Ares Management and that bought out all of the senior Class A Certificates upon an event of default), to sell the entire fleet of the Aircraft at an artificially depressed price of $250,000,000 to an affiliate of Ares Management’s parent company as a stalking horse bidder”.

The investors argue that the $250 million VMO Stalking Horse Bid amount – which is the total amount owed to the Class A Certificates holders plus fees and expenses owed to the liquidity provider, subordination agent, and any trustee – was substantially less than two of the post-default appraisal valuations of the aircraft—the highest of which was $289.2 million. The investors state that the bid amount was “designed to preclude any recovery on the Class B Certificates and solely benefit Ares, whose parent controlled the VMO Stalking Horse Bidder”.

The complaint also highlights several procedures in the Stalking Horse bid offer that the investors say were “highly unusual” for aviation sales and had the additional effect of “chilling competitive bidding”. The procedures highlighted include the accelerated timeline of just 26 calendar days to sell the aircraft, which the investors state discouraged competitive bidding that was exacerbated by the lack of adequate marketing that further limited potential bidders. The investors also claim that the terms of sale discouraged potential bidders. There were several unusual aspects noted here, foremost that bidders were required to submit a minimum bid of $280 million—$30 million in excess of the $250 million stalking horse bid—to account for a minimum overbid increment of $5 million as well as a break-up fee of $25 million for the stalking horse bidder. Potential bidders were also required to place a 10% cash deposit, and prove their financial capability to close on the transaction. The aircraft were also offered as a group on an “as is, where is” basis that the investors argue also deterred more potential bidders.

The complaint also reveals a hitherto unreported second alternative Stalking Horse bidder, which it states was led by leading industry experts, backed by one of the world’s largest private multi-asset alternative asset managers with $130bn AUM, that had formed a $1bn aircraft warehouse facility with the specific purpose of purchasing and storing aircraft. The investors argue that this alternative bidder was qualified and would have generated proceeds for the benefit of non-Ares Class B Certificate Holders but notes that this bidder wasn’t considered by Ares or VMO. Finally, the complaint highlights the fact that despite the collateral being the highly liquid Boeing 737-800NG aircraft, there were no bidders and the sales process was closed and the auction cancelled, declaring the stalking horse bidder as the successful bidder.

The investors are claiming damages of no less than $14.279 million in losses plus costs, and state that additional punitive damages should be awarded because “Ares and Vmo’s conduct was malicious, intentional, and undertaken in bad faith with a conscious indifference to Plaintiffs’ rights and interests”. With the seven courses of action noted in the complaint, the investors are seeking to hold the defendants accountable for their “egregious misconduct and failure to comply with their obligations arising under the governing contracts, Article 9 of the New York Uniform Commercial Code, and other applicable law”.

Ares, VMO and Wilmington Trust have all been contacted for comment relating to this story but none had responded at the time of publishing.

In the meantime, a second similar stalking horse bid has been launched by Sajama Investments, LLC for LATAM’s rejected fleet of 17 aircraft: 11 A321-200, two A350-900, and four 787-9s, used a security for its EETC Series 2015-1 A-C notes. A foreclosure sale process has been launched for these aircraft with notably similar terms of sale to the NAS 2016-1 stalking horse bid. The controlling party – Sajama Investments – has insisted that all of the aircraft should be included in a bid, and that each bid must be equal to or greater than the sum of the Stalking Horse Purchase Price of $276,250,000 and include a break-up fee of $21,250,000. There is also a minimum $5 million overbid increment provision, a 10% cash deposit requirement and all bidders must meet qualifying criteria and prove their ability to meet the financial obligations of their bid. The bid deadline for this sale is June 22, with a July 8, 2021 closing date.

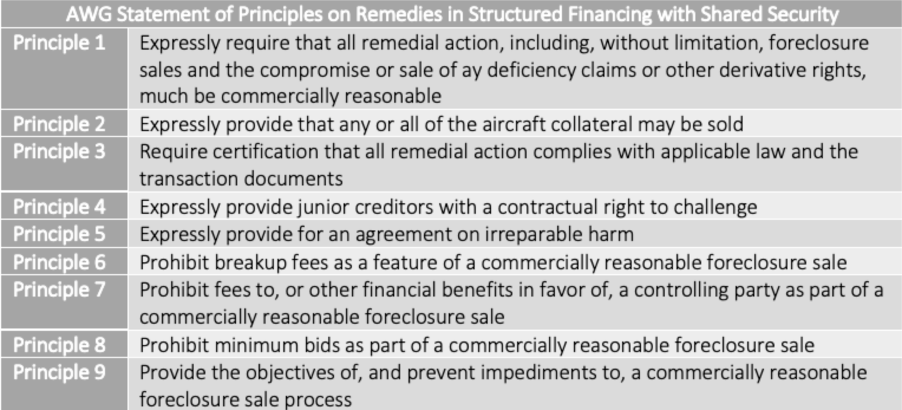

In a separate but related move, the Aviation Working Group has published a statement on guiding principles on remedies in structured financings with shared security interest over aircraft. Although the principles do not refer specifically to the contested NAS 2016-1 EETC foreclosure sale or indeed the ex-LATAM aircraft sale, they do address the substance of the actions made in the complaint and provide a route forward for transactions with shared security, such as EETCs.

The AWG guiding principles expressly require that all remedial action, including foreclosure sales, “must be commercially reasonable”. The AWG highlights the fact that although the UCC requires that all aspects of a foreclosure sale be commercially reasonable, it does not provide specific relief for junior creditors that share in a single security interest if a sale does not comply with these requirements. Since the UCC does not directly address the point that once the aircraft are sold, any deficiency claim is for the benefit of the creditors of all classes remaining unpaid, nor that the party in control of remedies should not be permitted to compromise, sell or dispose of such claims except in a commercially reasonable manner, that this should be included in all contractual agreements.

Principle 2 expressly provides that “any or all of the aircraft collateral may be sold”, highlighting that the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) does not require or preclude aircraft to be sold as a group. The AWG points out that many intercreditor agreements include ambiguous requirements to sell “all” of certain types of collateral, but the intention is that “all” means “all or part”. AWG recommends that should be made express to be clear that any or all aircraft may be sold in one or more sales and that all sales must be commercially reasonable. Only then would junior creditors be provided with contractual rights that mirror the UCC and give them a basis for enforcing such rights contractually.

Principle 6 specifically seeks to prohibit break-up fees as a feature of commercially reasonable foreclosure sale, which featured prominently in the NAS 2016-1 foreclosure case, and Principle 7 goes further to prohibit fees or financial benefits to controlling parties in a foreclosure sale. The AWG principles also seeks to prohibit minimum bids and prevent any impediments to a commercially reasonable foreclosure sale process.

Whatever the result of the litigation, the AWG principles and the market reaction to these sorts of deals will likely eventually result in new and tighter intercreditor contractual agreements going forward. We will be following the case with interest.